Nature Notes

Why is the Grand Canyon up to 18 miles wide if the river is only hundreds of feet in width?

When a river reaches a low-lying plain, it meanders widely. In the vicinity of a river bend, deposition occurs on the convex bank (the bank with a smaller radius). In contrast, both lateral erosion and undercutting occur on the cut bank or concave bank (the bank with the greater radius.) Continuous deposition on the convex bank and erosion of the concave bank of a meandering river cause the formation of a very pronounced meander with two concave banks getting closer. The narrow neck of land between the two neighboring concave banks is finally cut through, either by lateral erosion of the two concave banks or by the strong currents of a flood. When this happens, a new straighter river channel is created and an abandoned meander loop, called a cut-off, is formed. When deposition finally seals off the cut-off from the river channel, an oxbow lake is formed. This process can occur over a time scale from a few years to several decades and may sometimes become essentially static. When one takes this scenario and adds geologic uplift, like we have with the Colorado Plateau, we see entrenched meanders (river meanders with in a canyon). Buttes form by the meandering of entrenched rivers. The convex banks of the San Juan may create buttes of the future.

When a river reaches a low-lying plain, it meanders widely. In the vicinity of a river bend, deposition occurs on the convex bank (the bank with a smaller radius). In contrast, both lateral erosion and undercutting occur on the cut bank or concave bank (the bank with the greater radius.) Continuous deposition on the convex bank and erosion of the concave bank of a meandering river cause the formation of a very pronounced meander with two concave banks getting closer. The narrow neck of land between the two neighboring concave banks is finally cut through, either by lateral erosion of the two concave banks or by the strong currents of a flood. When this happens, a new straighter river channel is created and an abandoned meander loop, called a cut-off, is formed. When deposition finally seals off the cut-off from the river channel, an oxbow lake is formed. This process can occur over a time scale from a few years to several decades and may sometimes become essentially static. When one takes this scenario and adds geologic uplift, like we have with the Colorado Plateau, we see entrenched meanders (river meanders with in a canyon). Buttes form by the meandering of entrenched rivers. The convex banks of the San Juan may create buttes of the future.

The width of the canyon has everything to do with the erosive force of the Colorado River. Even though the river is only hundreds of feet wide, it meanders. The meandering of rivers widen their floodplains. An entrenched river is a river that is confined to a canyon or gorge, usually with a relatively narrow width and little or no floodplain and often with meanders worn into the landscape. Such rivers form when an area is elevated rapidly or for some other reason the base level of erosion is rapidly lowered, so that the river begins downcutting into its channel faster than it can change course (which rivers normally do on a constant basis). If the river had pronounced meanders before the lowering of the base level of erosion, then those meanders may become entrenched. At Grand Canyon, 5 million years of meandering and down cutting has widened the canyon. Additional widening has occurred with erosion from the side canyons.

Cinder Cone Volcanoes 101: How Sunset Crater Formed

To make a cinder cone, like Sunset Crater, you need to have lava with lots of gas. Gas-rich lava expands as it travels toward the surface. If you shake up a soda, then open it, you can simulate this effect. Open the can, or unplug the volcano, and you release the pressure that holds the gas in and the molten rock sprays into the air as a fiery fountain. Another analogy would be a spray paint can filled with gas and lava with the nozzle pointing out of the ground.

To make a cinder cone, like Sunset Crater, you need to have lava with lots of gas. Gas-rich lava expands as it travels toward the surface. If you shake up a soda, then open it, you can simulate this effect. Open the can, or unplug the volcano, and you release the pressure that holds the gas in and the molten rock sprays into the air as a fiery fountain. Another analogy would be a spray paint can filled with gas and lava with the nozzle pointing out of the ground.

That brings us to the second critical cinder cone ingredient, runny lava. Only very fluid lava with lots of gas can be sprayed hundreds of feet into the air as lava globs to form a nice cone. Magnesium and iron-rich (Mafic) lava is exactly the right consistency. It has a low silica content, so it is very runny (the amount of silica in molten rock determines how runny or thick the lava will be). The Mafic lava that erupted to make the Sunset Crater cinder cone made its way to the surface through a deep fracture that tapped a magma-filled pocket (magma-chamber) beneath the sedimentary layers you've seen at the Grand Canyon. Rather than spewing from a single vent, lava gushed onto the scene where this deep fracture cut the surface. A glowing 'curtain of fire' may have extended over several miles before eruptions focused their attention on the vents that built Sunset Crater Volcano.

As the outpouring of lava became focused beneath what is now Sunset Crater, lava fountains threw small blobs of molten basalt hundreds of feet into the air. Although lava erupted at 1200° centigrade (2200° Fahrenheit), most airborne molten globs cooled and solidified to form cinders before they reached the ground. Most cinders fell very near the central vent, building a small cone. Layer upon layer of volcanic ejecta are laid down, building a higher and steeper cinder cone. Eventually, the cone gets so steep that the sides collapse under their own weight. The collapsing cinders come to rest when they reach just the right steepness to keep them stable. This angle, usually about 35°, is called the angle of repose. Every pile of loose particles has a unique angle of repose, depending upon the material it's made from. Because cinders everywhere tend to have nearly the same angle of repose, cinder cones everywhere develop very similar cone shapes with nice, straight sides rising at an angle of about 35° from the ground. Cinder cones can grow very large, even wider in diameter than their maximum ejection distance. How can this happen? As cinders continue to pile high near the central crater, they will continually collapse. Eventually, the collapsing sides can spread a considerable distance beyond the 'throwing distance' of the cone-but they always maintain the same straight sides at just the right shape.

Cultural Landscape of the Southwest - 16th Century: 11/01/08

By the time the Spanish Conquistadors arrived, the Puebloan peoples had abandoned more than 50 percent of their ancestral homelands, which once encompassed more than 200,000 square miles. They had vacated the marginal agricultural lands of the basin and range country of southern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas, northern Chihuahua and northern Sonora. They had left the stream-dissected mesas and arid grasslands of the Colorado Plateau virtually uninhabited. It looked to the Spaniards as if the Ancestral Puebloan People left in such a hurry; they did not have the time to take any belongings.

By the time the Spanish Conquistadors arrived, the Puebloan peoples had abandoned more than 50 percent of their ancestral homelands, which once encompassed more than 200,000 square miles. They had vacated the marginal agricultural lands of the basin and range country of southern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas, northern Chihuahua and northern Sonora. They had left the stream-dissected mesas and arid grasslands of the Colorado Plateau virtually uninhabited. It looked to the Spaniards as if the Ancestral Puebloan People left in such a hurry; they did not have the time to take any belongings.

By the 16th century, in the southwestern United States, Puebloan peoples had congregated in some 100 communities, most within the upper drainage basins of the Gila River, the Little Colorado River, and the Rio Grande. These included the villages of the Zuni, on the Zuni River in west central New Mexico, near the Arizona border; the Hopi, on the southern escarpment of Black Mesa, in northwestern Arizona; the Acoma and Laguna, in the arid canyon and mesa country of west-central New Mexico; and the eastern Puebloan peoples, along the mainstream and tributaries of the Rio Grande, in north-central New Mexico. New immigrant populations confronted unfamiliar landscapes, new neighbors, and differing traditions. They not only had to build new homes and cultivate new fields, but they also had to reinvent themselves culturally and collectively in terms of their fundamental beliefs, language, political and organizational structures, religion and ceremony, architecture, arts and crafts, and trade relationships.

The History of Phantom Ranch - Grand Canyon: 11/15/08

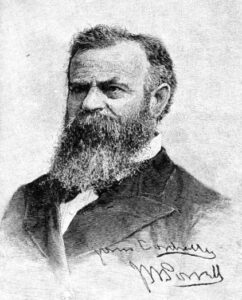

The site where the resort is now located was used by Native Americans; pit houses and a ceremonial kiva dating from about 1050 AD have been found there. The earliest recorded visit by Europeans took place in1869 when Powell and his company camped at its beach. Prospectors began using the area in the 1890s, using burros to haul their ore.

The site where the resort is now located was used by Native Americans; pit houses and a ceremonial kiva dating from about 1050 AD have been found there. The earliest recorded visit by Europeans took place in1869 when Powell and his company camped at its beach. Prospectors began using the area in the 1890s, using burros to haul their ore.

At the turn of the century, the founders of the Grand Canyon Transportation Company began a project to exploit its tourism potential; they hired a crew to improve the trail from Phantom Ranch to the Canyon's North Rim. President Roosevelt traveled down the canyon to the camp during a hunting expedition in 1913; in honor of this visit, the site became known as Roosevelt Camp.

Roosevelt's enthusiasm for the Grand Canyon helped lead to its incorporation into the National Park System in 1919. The Fred Harvey Company was granted the concession for the camp in 1922; the company hired the American architect Mary Colter to design permanent lodging. Mary Colter suggested that its name be changed to Phantom Ranch. Construction presented a major challenge: all building materials except for rock had to be hauled down by mules. Meeting the challenges at this and other national parks led to the architectural style known as National Park Service rustic, which features native stone, rough-hewn wood, large-scale design elements, and intensive use of hand labor.

Ancestral Puebloan Peoples of the Southwest: 12/01/08

At around 700AD, we see a distinct cultural group forming from the Basketmakers. Like their cultural kin – the Mogollon, Sinagua, and the Hohokam – in the deserts to the southwest, the earliest Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloan Peoples) felt the currents of revolutionary change during the first half of the first millennium. In response to Mesoamerican influences from Mexico (technological with regard to agriculture – economic with regard to trade – cultural), they began to turn away from ancient hunting and gathering life. They began living in small villages. They cultivated the land and took up agriculture. Over time, they acquired more possessions, stored food, made pottery, domesticated dogs and turkeys. They still hunted and gathered, not as their only avenues for acquiring food, but as a complement to cultivated corn, beans, squash, and other crops.

At around 700AD, we see a distinct cultural group forming from the Basketmakers. Like their cultural kin – the Mogollon, Sinagua, and the Hohokam – in the deserts to the southwest, the earliest Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloan Peoples) felt the currents of revolutionary change during the first half of the first millennium. In response to Mesoamerican influences from Mexico (technological with regard to agriculture – economic with regard to trade – cultural), they began to turn away from ancient hunting and gathering life. They began living in small villages. They cultivated the land and took up agriculture. Over time, they acquired more possessions, stored food, made pottery, domesticated dogs and turkeys. They still hunted and gathered, not as their only avenues for acquiring food, but as a complement to cultivated corn, beans, squash, and other crops.

In the first half of their history, the Anasazi distinguished themselves primarily through the artistry of their basketry, which they crafted from the fibers of plants. In the second half, they left their mark on a much grander scale, through the construction of perhaps the most stunning prehistoric communities in the United States. The Anasazi would prove to be resourceful, adaptable, and, ultimately, the most enduring of the Pueblo cultural traditions.

By 1400AD, all archaeological sites of the Sinagua and Anasazi were abandoned. Just as the Puebloan People reached their cultural pinnacle across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, they began to grow restless in their respective ancestral homelands. They began to break the bonds with their traditional and historic ranges and long-established trade routes. Forsaking the great physical and spiritual investments by generations, they walked away from their homes and their lands with no more than what they could carry on their backs.

Between 1150 and 1450, the Puebloans simply abandoned an unprecedented region, primarily the vast expanses of marginal farming areas which encompassed canyons, mesa tops, open grasslands and desert basins in the Four Corners region, eastern Arizona, western New Mexico and northern Mexico. Some apparently moved southward into the vicinity of Arizona’s Hopi pueblos and New Mexico’s Zuni, Acoma and Laguna pueblos. Many others continued to locations still farther south and east. Many of the Mesa Verde Anasazi people moved southeastward into the upper Rio Grande drainages.

In the end, we still don’t fully understand what prompted so many people across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico to give up ancestral homelands and move, en masse, to new regions within the same period. There is no evidence of war, major natural disasters, or plague-like disease. We do know that drought hit the region, possibly causing these ancient Puebloan peoples to abandon in search of water sources; BUT… where did they go? We can guess that communities felt "pushed" by some combination of social and environmental factors and "pulled" by promises of more stable weather, irrigable farmland, safer communities and spiritual fulfillment. We may never understand, however, how the phenomenon of abandonment and migration extended over such a wide area at the same period in prehistoric times.

Pangaea and the Permian Extinction: 01/01/09

The uppermost rock strata in Sedona and the Grand Canyon’s geologic section is the Kaibab Limestone. It is the last or rather, the youngest of the Permian formations in this region. The Kaibab is rich in marine fossils and more significantly, locally, marks the end of a 300 million year era called The Paleozoic. With the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea in the Permian, continental area exceeded that of oceanic area for the first time in geological history. The result of this new global configuration was the extensive development and diversification of Permian terrestrial animals and the accompanying reduction of Permian marine communities.

The uppermost rock strata in Sedona and the Grand Canyon’s geologic section is the Kaibab Limestone. It is the last or rather, the youngest of the Permian formations in this region. The Kaibab is rich in marine fossils and more significantly, locally, marks the end of a 300 million year era called The Paleozoic. With the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea in the Permian, continental area exceeded that of oceanic area for the first time in geological history. The result of this new global configuration was the extensive development and diversification of Permian terrestrial animals and the accompanying reduction of Permian marine communities.

The Permian mass extinction occurred about 248 million years ago and was the greatest mass extinction ever recorded in earth history; even larger than the Ordovician and Devonian crises and the better-known End Cretaceous extinction that felled the dinosaurs. Ninety to ninety-five percent of marine species were eliminated as a result of this Permian event. The therapsids (mammal-like reptiles – precursors to the dinosaurs) managed to survive this mass extinction with their ability to borrow into the ground. It is universally accepted that the Permian extinction opened the way for the impressive evolution of the Dinosauria.

Speculated Causes of the Permian Extinction - Although the cause of the Permian mass extinction remains a debate, numerous theories have been formulated to explain the events of the extinction. One of the most current theories for the mass extinction of the Permian is glaciation. A similar glaciation event in the Permian would likely produce mass extinction in the same manner as previous, that is, by global widespread cooling and/or worldwide lowering of sea level.

The Formation of Pangea - Another theory that explains the mass extinctions of the Permian is the reduction of shallow continental shelves due to the formation of the super-continent Pangea. Such a reduction in oceanic continental shelves would result in ecological competition for space, perhaps acting as an agent for extinction. However, although this is a viable theory, the formation of Pangea and the ensuing destruction of the continental shelves occurred in the early and middle Permian, and mass extinction did not occur until the late Permian.

Glaciation - A third possible mechanism for the Permian extinction is rapid warming and severe climatic fluctuations produced by concurrent glaciation events on the north and south poles. In temperate zones, there is evidence of significant cooling and drying in the sedimentological record, shown by thick sequences of dune sands and evaporites, while in the polar zones, glaciation was prominent. This caused severe climatic fluctuations around the globe, and is found by sediment record to be representative of when the Permian mass extinction occurred.

Volcanic Eruptions - The fourth and final suggestion that paleontologists have formulated credits the Permian mass extinction as a result of basaltic lava eruptions in Siberia. These volcanic eruptions were large and sent a number of sulfates into the atmosphere. Evidence in China supports that these volcanic eruptions may have been silica-rich, and thus explosive, a factor that would have produced large ash clouds around the world. The combination of sulfates in the atmosphere and the ejection of ash clouds may have lowered global climatic conditions. The age of the lava flows has also been dated to the interval in which the Permian mass extinction occurred.

Grand Canyon Deer Roundup: 02/01/09

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt established the Grand Canyon National Game Preserve on the Kaibab Plateau. His intention was to protect the mule deer from overhunting by humans and predation by natural enemies. He knew that human activities had depleted wildlife species throughout the country, and only a few locations in the West still contained the numbers that had flourished a few decades earlier.

The United States Forest Service administered the new preserve as it had the surrounding forest lands since the 1890s. Ranchers grazed fewer domestic animals there for a combination of reasons, including degraded forage conditions and reduced permits from the Forest Service. The mandate of the preserve prohibited all deer hunting on the plateau and at the same time exterminated "varmints" such as mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, and wolves. Bounty hunters diligently tracked and killed mountain lions, which they viewed as the most significant enemy of the deer. Wolves were already rare by 1900, having been almost completely exterminated by ranchers before the turn of the century. Each year, local Forest Service officials estimated that there were more deer on the plateau than in the previous year.

Unfortunately, a combination of the reduction of predators along with overgrazing and the ensuing dust bowl, proved disastrous for the Kaibab mule deer population. With depleted grasses due to grazing and the drier climate, deer populations were searching for food wherever they could find it - stripping trees for forage.

In the fall of 1924, the Forest Service chose a combination of options for reducing the deer population, starting with hunting. They opened the plateau to hunters without the permission of the state of Arizona - leading to a series of arrests - and without even notifying the National Park Service of their intentions. The Forest Service tried its second option by organizing an effort to drive some of the deer off the plateau, into the Grand Canyon, across the Colorado River, and up to the South Rim.

In the fall of 1924, the Forest Service chose a combination of options for reducing the deer population, starting with hunting. They opened the plateau to hunters without the permission of the state of Arizona - leading to a series of arrests - and without even notifying the National Park Service of their intentions. The Forest Service tried its second option by organizing an effort to drive some of the deer off the plateau, into the Grand Canyon, across the Colorado River, and up to the South Rim.

Zane Grey, the famous western writer, promoted and participated in this drive. Despite the assistance of local ranchers and Native Americans, the attempt failed completely. Deer, as many experienced ranchers and naturalists well knew, do not congregate and move in large groups like cattle or sheep. This flurry of activity on the Kaibab Plateau brought unprecedented fame to the emerging controversy there. Popular articles appeared in many of the nature and sporting magazines of the time. The involvement of a famous author, heads of several federal agencies, and numerous well-known biologists captured the public's interest.

Because action to reduce the deer had been too little and too late, many scientists and Forest Service officials predicted that deer would starve by the thousands. While few carcasses of starved or frozen deer were actually found, most visitors to the area the following spring reported seeing fewer deer than in previous years. Many supposed that undernourished deer became easy prey for coyotes or died in rough terrain where no one ever found them. From this indirect and generally unreliable evidence, the deer herd's ruin became established.

Excerpts: History of the Kaibab Deer, Chris Young

Camel Ghosts in Arizona: 02/15/09

Following the end of the Mexican War in 1848, the U.S. had its claims on Texas and California recognized and also acquired much of what is now Arizona and New Mexico. However, with the acquisition of the harsh desert land, the Army faced the problem of both defending it and supplying the forts that were built to defend it. Horses and mules tended to give out in this land and an alternative and more reliable means of transportation was needed.

Following the end of the Mexican War in 1848, the U.S. had its claims on Texas and California recognized and also acquired much of what is now Arizona and New Mexico. However, with the acquisition of the harsh desert land, the Army faced the problem of both defending it and supplying the forts that were built to defend it. Horses and mules tended to give out in this land and an alternative and more reliable means of transportation was needed.

Jefferson Davis either came up with the idea, or liked the idea when someone else suggested it, of importing camels to use as beasts of burden in the desert. In 1855 he dispatched Major Henry Wayne to Europe and the Middle East o learn about camels and purchase some for use in Arizona. Major Wayne met with Hi Jolly (actually Hadji Ali) who was a specialist in driving camels and was one of the first camel drivers ever to be employed by the US Army. It is believed that he was born somewhere in Syria around 1828 but there is no record of what his Greek mother and Syrian father named him, he took the name Hadji Ali when he converted to Islam during his early life. He changed his name from Hadji Ali to Hi Jolly to help the soldiers with his name, they had problems pronouncing and remembering Hadji Ali.

Major Wayne made the trip and returned home with 33 camels which were used to create the U.S. Army Camel Corps. Actually, the camel idea did work for the Army and, for a few years before the Civil War the Camel Corps did roam the deserts of Arizona as well as the deserts of California, Nevada and Utah. In fact camels proved to be so reliable as beasts of burden in the desert that the Army imported some more and mining companies also acquired some for use in remote desert mines.

However, with the start of the Civil War, the War Department had other needs besides camels and, as troops were pulled from the West to the battle fields of the East the camels were left behind. Some were sold and used by mining companies or circuses while others ended up being abandoned in the desert and reverting to a wild state. Between the low numbers to begin with plus reductions in the wild camel population by hunters, wild camels were never able to establish themselves like the wild horses (mustangs) that multiplied and roamed the west. Instead the camels simply died out. However, according to legend, the ghosts of some of these camels can sometimes still be seen at night wandering in the deserts of the Navajo Reservation.

Grand Canyon National Park – 90 Year Anniversary: 03/01/09

In 1887, U.S. Senator Benjamin Harrison introduced legislation to establish the Grand Canyon as a national park, but he bill failed due to economic interests in the area. When he became president, Harrison designated the land a National Forest Preserve on February 20, 1893. This protected the park in some ways, but mining and logging were still permitted.

In 1887, U.S. Senator Benjamin Harrison introduced legislation to establish the Grand Canyon as a national park, but he bill failed due to economic interests in the area. When he became president, Harrison designated the land a National Forest Preserve on February 20, 1893. This protected the park in some ways, but mining and logging were still permitted.

After a visit by President Teddy Roosevelt in 1903, additional protection was added, which culminated in designation of the park as a United States National Monument on January 11, 1908. Mining was still allowed and thwarted effort to establish it as a National Park until eleven years later.

On February 26, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson signed the law making Grand Canyon National Park the 17th park in the nation. Various changes in the size of Grand Canyon National Park have taken place over the years, with the merging of additional lands in the federal system into one entity by President Ford, as well as the deletion of Havasu Canyon when given back to the Havasupai Indians.

The Principal of Uniformitarianism 'the present is the key to the past’: 03/15/09

Our region is essentially defined by its abundance of Sedimentary Rocks. These rock types are deposited in environments in which sediment accumulate. Therefore, when one knows how to read clues in these ancient rock layers, one can essentially interpret the past environments in which they formed. To do this successfully, geologists must make the assumption that the processes acting on our planet today are the same processes that have always acted on our planet. This is one of the main tenets in Geology: The principal of Uniformitarianism.

Our region is essentially defined by its abundance of Sedimentary Rocks. These rock types are deposited in environments in which sediment accumulate. Therefore, when one knows how to read clues in these ancient rock layers, one can essentially interpret the past environments in which they formed. To do this successfully, geologists must make the assumption that the processes acting on our planet today are the same processes that have always acted on our planet. This is one of the main tenets in Geology: The principal of Uniformitarianism.

As rivers flow over the surface of Earth, they cut canyons in some places and deposit sediments in other places. Geologists make the assumption that rivers flowing in the past must have behaved in the same ways as rivers that flow today. For another example, at an active volcano we can observe lava cooling to form layers of basalt. Therefore, any time we see layers of basalt, we can assume that they formed from cooling lava.

To explain further: by looking at the Sedimentological processes of today and the features produced by them we can draw inferences that will tell us about the conditions in which ancient rocks were laid down. For example, we’ve all seen ripple marks on beaches; these are caused by sand particles being moved about by the ebb and flow of a shallow tidal environment. It follows, therefore, that rocks found in our region like the Moenkopi Shale, which show ancient ripple marks, must have been laid down in a similar environment.

The Great Pueblo Revolt: 04/01/09

In January 1998, some one sawed off the right foot of a 12-foot bronze statue of Don Juan de Oñate at the Center in Alcalde, New Mexico, to protest the celebration of the Spanish conqueror's arrival in New Mexico. In a battle against the Acoma Indians on January 22, 1599, the Spaniards lost 12 men while killing more than 800 Indians. Oñate proceeded to order a foot cut off every male 25 years and over in the pueblo. Males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sentenced to 20 years of hard labor.

In January 1998, some one sawed off the right foot of a 12-foot bronze statue of Don Juan de Oñate at the Center in Alcalde, New Mexico, to protest the celebration of the Spanish conqueror's arrival in New Mexico. In a battle against the Acoma Indians on January 22, 1599, the Spaniards lost 12 men while killing more than 800 Indians. Oñate proceeded to order a foot cut off every male 25 years and over in the pueblo. Males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sentenced to 20 years of hard labor.

A later incident in 1675 served as the compelling motivation for the big Pueblo rebellion. The Spanish arrested 47 medicine men, publicly whipping them and hanging four in the plaza of Santa Fe. In the group of the survivors was one man who had enough of the Spaniards' cruel injustices and would become their worst adversary. His name was Popé. Popé, whose name meant "Ripe Squash," was born a Tewa Indian in the village of Grinding Stone in the San Juan Pueblo on the Rio Grande. In a fashion that seemed foreign to the peaceful Pueblo Indians, Popé wished to forcefully drive the Spanish out of New Mexico due to the bloody and violent suppression of native religions, their brutal exploitation of Indian labor and frequent slave raids.

At the appointed time, communicated via knotted cords, the pueblo Indians killed over 400 Spanish friars, troops and settlers were killed, and their missions burnt. Finally, they besieged Santa Fe together with their Apache allies demanding the release of all Indian slaves and Spain's abandonment of New Mexico, forcing the governor to flee. Apart from the occasional Spanish raid, they would remain free for the next 13 years.

In 1693 Diego De Vargas, the new governor retook Santa Fe and began a war of attrition against the Pueblos. Those that submitted to Spanish rule had priests appointed to administer them, those that didn't were stormed, their women and children enslaved and the men shot or hanged. Many fled to the neighboring Navajo and Apache lands for protection or to the Pueblos that held out against the Spanish. Although the revolt was finally put down in 1698, the Spanish were never able to fully subdue the Hopi again.

Major John Wesley Powell: 04/15/09

“We are now ready to start on our way down the Great Unknown. Our boats, tied to a common stake, chafe each other as they are tossed by the fretful river… We have but a month’s rations remaining. The flour has been resifted through the mosquito-net sieve; the spoiled bacon has been dried and the worst of it boiled… We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we known not. Ah, well! we may conjecture many things.” Powell's Expedition Log – Aug. 13, 1869

After the civil war, Major John Wesley Powell petitioned the U.S. Government to sponsor an expedition to float the entire length of the Colorado River and explore its tributaries. The United states had recently acquired the Southwest Territories from Mexico but did not know the geography of the acquisition - maps and surveys needed to be made.

After the civil war, Major John Wesley Powell petitioned the U.S. Government to sponsor an expedition to float the entire length of the Colorado River and explore its tributaries. The United states had recently acquired the Southwest Territories from Mexico but did not know the geography of the acquisition - maps and surveys needed to be made.

The 1869 expedition started on the Green River and continued down to the confluence of the Grand River flowing west into Utah. The two mighty rivers then merged into the Colorado, Spanish for red river. When it rained the side tributaries spilled their muddy red sediment into the clear green waters of the main channel causing it to run red and thick with silt. River runners described the Colorado in the days before Glen Canyon Dam as "too thick to drink and too thin to plow."

Early on in the journey, the expedition suffered the loss of half of their supplies and a boat during a pounding received from a massive set of rapids near Cataract Canyon. During the next two months on the river, the men encountered many more rapids that could not be run safely in Powell's estimation. Powell was fearful they would lose the rest of the supplies and perhaps even their lives. So they lined the boats down the side of the rapids, or portaged boats and supplies through the rocks along the shoreline.

At a place now called Separation Canyon, O.G. Howland, his brother Senaca, and Bill Dunn came to the Major and spoke of "how we surely will all die if we continue on this journey." They could only see more danger ahead and desperately tried to convince Powell to abandon the river. The next morning, the three men said their goodbyes to Powell and the remaining five adventurers. Powell left his boat the Emma Dean at the head of Separation Rapid in case they changed their minds. With the other five men Powell ran what would turn out to be the first of two remaining major rapids they would encounter.

The Howlands and Dunn climbed out of the canyon walking towards civilization only to meet their death at the hands of Shivwits Indians who mistook them for miners that had killed a Hualapai woman on the south side of the river. At least that was the story Powell heard the next year when he visited the Shivwits area with Mormon Scout Jacob Hamlin. Ironically, two days after the man abandoned the expedition, Powell and his men reached the mouth of the Virgin River (now under Lake Mead) and were met by settlers fishing from the river bank. The adventurers had not been heard from in three months and were presumed dead.

Powell had completed what he sought to do ... explore and confirm his theory on the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, a region up to that time almost wholly unknown and concerning which there were many vague and often wild rumors. His theory was the river preceded the canyons and then cut them as the Plateau rose.

Returning a national hero to Illinois, Powell promptly hit the lecture circuit then raised funds for a second expedition in 1871 which would produce what the first did not -- a map and scientific publications. In March 1881, he founded and assumed the first directorship position of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Book your tour Now

Toll Free: 866.473.3786 | Direct: 928.203.0396

![]()